At a recent seminar I attended, titled ‘The Future of Medicine,’ I was thrust into a whirlwind of advanced concepts and prognostications about what healthcare might look like in the not-too-distant future. It’s a topic that marries my worlds of medicine and narrative in a dance of both possibility and peril. I was partly, cynical. All of this innovation, and working in the NHS, we can’t even get the basics right, such as operating lists and handling patient data.

Woody Allen once quipped, ‘If you want to live until you’re 100, then you have to give up all the things that make you want to live until 100.’ This witticism, delivered with the typical Allen-esque deadpan, encapsulates the poignant irony of our modern quest for longevity. Indeed, we’re biologically wired for reproduction rather than for durability, yet here we are, pushing the very boundaries of human life expectancy.

A while back, headlines declared that excessive consumption of sausages could lead to an early demise. There are many things I could forego, but giving up Walls pork sausages? They’d have to pry them from my cold, dead hands.

At the heart of the seminar was an exploration of how modern medicine is pivoting towards incredibly specific, targeted treatments. We’re talking about a world where your medications are tailored to the genetic nuances of your individual physiology. Imagine drugs that are designed not just for a condition, but for your version of that condition. This isn’t just personalised medicine; it’s personalised medicine at a granular level that would have seemed like science fiction just a few decades ago.

Then, there’s the rise of robotics and artificial intelligence in healthcare. And cobotics–a term I hadn’t heard of before.

Surgical robots, already a mainstay in our operating theatres, are growing more adept by the day, capable of executing intricate procedures with a precision that eclipses human capabilities. Meanwhile, AI is transforming diagnostics, rapidly analyzing immense datasets to identify patterns and anomalies that might escape even the most discerning experts.

Yet, the conversation extends beyond the machinery itself—it’s the broader implications of such technological leaps that captivate and concern us. At a recent seminar, the University of Georgia posited a provocative notion: someone alive today might exceed 120 years of age. This prospect is as thrilling as it is daunting. What are the societal, resource-based, and personal identity implications if a significant portion of our lifespan extends into what is currently considered ‘old age’?

This brings us to a pertinent question that often surfaces: Would you consent to an operation conducted by an autonomous robot? It’s worth considering this: while no surgeon is devoid of error, imagine a robot that operates with a near-zero complication rate. Would this assurance sway your trust away from human surgeons towards robotic precision?

Moreover, AI often receives a skeptical reception, conjuring up visions of a dystopian world akin to The Terminator. Yet, Mustafa Suleyman, in his insightful book The Coming Wave, urges Boomers and Gen X’ers to adopt a more nuanced view. Suleyman argues that the actual issue isn’t the AI itself but rather the intentions of those who control it. The real threat stems not from the machines but from those who might use them for harmful purposes. Shifting the focus from a fear of technology to a concern about the ethical direction of its human operators is essential for understanding the real stakes of AI development.

This push towards extending life comes with ethical, philosophical, and logistical questions. How do we ensure quality of life keeps pace with quantity of life? If the essence of life is indeed more about reproduction from a purely biological standpoint, what are the implications of extending life well beyond our reproductive years?

These questions are not just academic; they have practical implications for all of us, especially those of us in the medical field. As an Anaesthetic technician and author, I find these topics particularly fertile ground for exploration, both in my professional practice and in my writing. They force us to reconsider our narratives about what it means to live a good life and what it means to die.

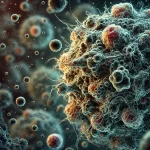

Furthermore, while there’s no panacea for cancer – and perhaps there never will be – the future does hold promise for more effective management of such diseases. Targeted pharmacology offers hope for turning terminal illnesses into chronic, manageable ones. This shift could transform the landscape of healthcare and our approaches to treatment.

In conclusion, the future of medicine is about more than just the tools and technologies; it’s about a fundamental shift in how we think about health, longevity, and our roles as caretakers of our own bodies. It compels us to ponder deeply on what it means to live not just a long life, but a life full of meaning. As we navigate these thrilling but uncharted waters, I remain optimistic about our capacity to face these challenges head-on, turning the ‘impossible’ into the inevitable.

So, let us march into this brave new world with our eyes wide open, ready to question, challenge, and embrace the future of medicine. After all, we are truly living our best lives, or at least, the best lives science and medicine can provide us. And isn’t that a story worth telling?