by Jon Biddle

A snapshot of a critical care practitioner.

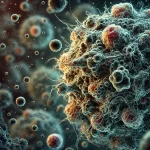

The consequences of sarcoidosis prevented me from being at the front end of the pandemic. Never walking away from a fight, but I had too. This caused a stir of emotions in me that made me reflect. I hope that we learn from the stay home, stay safe lockdown, and struggle to understand the thought process of some people about being ‘stuck at home.’ Clock the choice of words – safe at home – or stuck at home?

But after I had a conversation with a close friend of mine, I asked if I could narrate this conversation in a transcription on my blog. They agreed. They will, however, be anonymised as their location.

A snapshot of a critical care professional, in an acute hospital; UK.

The lead up to the Easter weekend, I had three days off, which I needed. I had been beasted for seven solid days. The patients were building in a level I had never seen before. This was on the back end of four tours in Afghan, three tours in Iraq and working in the Ebola crisis in Sierra Leone and the natural disaster of Haiti.

Three nights separated me and my Easter eggs from my wife and children.

I walked into the hospital thirty minutes before the shift started at 8PM. The atmosphere in the hospital had changed. We had seen a massive spike in admissions and a string of deaths. But the tone of the hospital was like DEFCON 3.

The critical care unit entrance, I counted fifteen gurneys, all with coarse breathing, blue tinged people, most in distress but weirdly, were still on their phones. All waiting for admission to my ward. I got into the unit which was the third ICU ward we had set up. The hand over was succinct, the day staff looked like they had been through the mill, most had no breaks and they had had their fill of coding patients with nothing that could be done. They needed to go home immediately and escape the madness.

The worst thing about all of this is the donning and doffing of PPE. It’s time consuming and exhausting. Your mind is constantly pushing you to take short cuts, but when you consider the viral load that was floating around the critical care units, short cuts meant you would be on the fast lane to a ventilator.

I had three patients to over see, buddying up and watching each others backs. The equipment was uncomfortable. The bridge of my nose at one point bled, my lips in a constant purse, trying to slowly draw air in so to not break the seal of the respirator. A habit I picked up in the fetid heat of Sierra Leone during the Ebola crisis.

Every night at around 2AM, all the patients would spike their blood pressure and temperature. This was the witching hour. The patients were taken from us, it was as though the reaper came to visit at this time every day. Another call to a relative. It doesn’t matter what time you make that call, the phone rings only once, then to deliver news that they had been dreading. That Thursday night, we lost on our ward, eight patient’s. We had intubated, and placed on a ventilator’s another 22, an unprecedented number.

By the time that I sat down with my children on Easter Sunday at breakfast and eat my eggs. The best time in the year for me. The sun seems to always shine; the birds sing their hearts out while the flowers are exploding like silent fireworks.

But my body was numb, exhausted. I couldn’t even speak, I was so emotionally withdrawn; I didn’t know if these were flashbacks from my time in the army, or the last three nights. The crying didn’t come until the privacy of my bedroom, but my eyes were brimming all the way home, and while I sat at the table. My mouth would twitch and tremble to force a smile, all the while trying to hold it together, I felt my soul weep in a way I didn’t think possible.

My wife knew, a veteran in her own right with the military tours that I had done. She handled it in a way that I just can’t express. I had signed off on over forty dead. I saw them all die a horrible death. A slow drowning. There were no heroics jumping on the chest, no shocks, no pushing drugs. I noticed one person, young. They had just died while the phone was still open. Three messages from a friend, asking why they hadn’t replied to the comment above. I see this flashing cursor each time I close eyes.

Everything disconnected and while the body cooled, their space was occupied with another blue breather. Another patient that was part of the six percenters that would throw the dice of luck with this virus. We silently moved on to the next, with nodding winks, chest pat’s, fist bumps and a silent love that was growing in me for every person who worked that night.

Mothers, fathers, children, grandparents, black, white. It didn’t matter who you was. It was the cruelest of the cruel. It showed no prejudice. I was numb to even judge the people not socially distance on the way home. I stare with horror with what is happening in America. Those poor people.

We don’t call for a fly past, or rounds of applause, although appreciated. What we lack is better pay and better conditions.

You wouldn’t ask a firefighter to enter a burning building without a breathing device, or send a soldier to war without a weapon. Yet the government seems to think it’s okay to let medical staff wear bin bags and paper masks as a form of PPE. What terrifies me more, is that the government can chop and modify the policies to suit their agendas, while these inconsistencies are killing us.

That weekend over Easter we saw one of our own die on our ward. And we still can’t take breaks, not because of staffing, which is another issue, but because there was no PPE to change into once you had had your break.

We all hope, in the NHS, when this will be finally over, that the gratitude that is overflowing, continues. Because if not, what would this all been for?

Sobering thoughts. This is a snapshot of thousands of my colleagues from around the world doing the job they love for little pay and benefits. The one thing I hope is that our government seriously takes a step back and addresses the shocking pay conditions the health sector has experienced over the last twenty years.

Murder Montly

Have you heard of Murder Monthly?

Murder Monthly is a subscription based short story, sent to you monthly. In that short story is the research from some societies’ most heinous killers. The twist of this is a fictional story that I have also included in the toe small eBook.

So if you like a bit of crime with your coffee or you find yourself at a loose end and some time to kill, hit the link.